Today marks the launch of the Data Workers‘ Inquiry. This joint project between the Weizenbaum Institute, the Technical University of Berlin, and the Distributed AI Research Lab, features workers behind artificial intelligence and content moderation discussing their working and living environments. The inquiries come in various forms, from texts to videos, podcasts, comics, and zines.

We asked co-initiator Milagros Miceli what lessons can be learned from the Data Workers‘ Inquiry. Miceli is a sociologist and computer scientist who leads a team at the Weizenbaum Institute in Berlin. She has been researching the work behind AI systems for years, including data annotation, where people sift through, sort, and label data sets so that machines can understand them. For instance, before an image recognition system can identify a photo of a cat, humans must label a series of images with cats. AI systems can then be trained with such data sets.

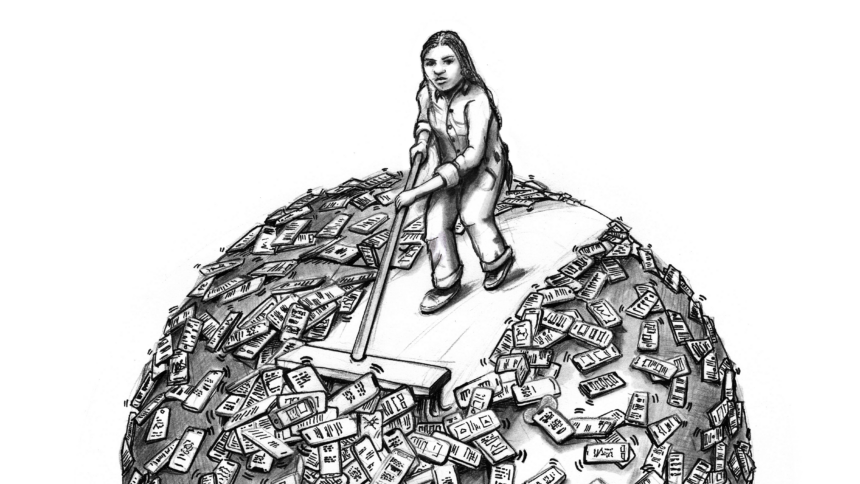

„The workers are treated as disposable“

netzpolitik.org: How important are data workers for the functioning of the digital world?

Milagros Miceli: Data workers are essential to the development and maintenance of the most popular platforms and systems we use. There’s no AI without the labor that goes into data collection, cleaning, annotation, and algorithmic verification. Without the continuous work of content moderators, who make social media platforms, search engines, and tools like ChatGPT usable, we wouldn’t be able to navigate these systems without getting seriously scarred, psychologically speaking. Would we still use ChatGPT if all its answers were filled with slurs? Would we still be on social media if we routinely encountered violent images?

netzpolitik.org: What role does outsourcing play in this industry?

Milagros Miceli: Human labor is a necessary part of the loop to generate and maximize surplus value. But for this, labor needs to be available and cheap. Hence, most tech giants rely on platforms and companies that provide an outsourced workforce, available 24/7 at low costs. The impressive advancement of AI technologies in the past decade or so correlates with the flourishing of data work platforms and companies that started with the creation of Amazon Mechanical Turk 20 years ago. The MTurk model made a large global workforce available at all times and at cheap prices.

netzpolitik.org: In the project, data workers report from very different work contexts and regions of the world—from platform workers in Venezuela or Syria to employees of outsourcing companies in Kenya and content moderators in Germany. Is there a universal experience that all of them share?

Milagros Miceli: These are the common realities of most data workers: they are paid for each task completed, not for their time; they receive meager hourly wages as low as 2 USD in Kenya or 1.7 USD in Argentina, and have no labor rights or protection; they are subject to surveillance and the arbitrariness of clients and platforms, and, in many cases, they carry permanent mental-health issues from the job. Most data workers are subject to NDAs that prevent them from talking to others about what’s going on. We have seen cases in which workers didn’t seek psychological or legal advice because they were told that would mean breaking the NDA.

Especially in the Global South, there are structural dependencies that leave workers with no option but to accept such working conditions. In places with high unemployment rates, the workforce remains constant, and workers are treated as disposable. The outsourcing model also helps companies avoid responsibility: when problems arise, nobody feels responsible for the workers‘ well-being, and they are left to suffer alone.

The workers themselves have their say

netzpolitik.org: The work of data workers behind AI and content moderation is often made invisible, which is why Mary Gray and Siddharth Suri also speak of Ghost Work. How does the Data Workers‘ Inquiry want to change this?

Milagros Miceli: Making this “ghost work” visible, shedding light on the problems faced by workers, and raising public awareness are important goals of our project. However, the Data Workers’ Inquiry embodies a commitment to go beyond just abstractly “raising awareness” in the sense of academics and journalists talking about the workers. Our approach is amplifying workers’ voices and political demands. Shifting away from us talking for and about the workers towards creating a platform where workers can talk for themselves and put things in their own words was very important to me in the conception of this project and methodology.

netzpolitik.org: What does this look like in practice?

Milagros Miceli: We invite the data workers to take the lead, both in deciding which topics and issues they consider pressing and in choosing the medium and format. The variety of the inquiries speaks for itself: there are podcasts, documentaries, animations, comics, zines, and essays. Most formats were decided upon specifically to reach wider audiences who don’t necessarily read academic papers.

Furthermore, we hope that the project’s dialogue and networking opportunities can strengthen workers’ organization efforts and lead to positive changes. So it is not only about workers informing us but also about workers talking to each other and organizing.

netzpolitik.org: The participating data workers act as „community researchers“ in the project. What exactly is their role?

Milagros Miceli: This means that they conduct research within their own worker communities or workplaces as community members themselves, that is, from an insider perspective. We center their experiences and recognize their unique knowledge. In my career, I’ve conducted around 100 interviews with data workers globally. Still, I will never know how it feels to be dependent on this work and mistreated by clients. This is something that only workers can know.

Each community researcher develops unique research questions, designs and conducts their inquiries, and prepares a presentation format for their findings. In the process, they talk to their co-workers and other data workers and are also in constant exchange with us. For instance, we offer advice on how to collect data and structure the process. Our job is to organize and provide a platform for these inquiries and to constantly evaluate their ethical and legal boundaries.

„The workers risk a lot“

netzpolitik.org: What effect does this have on the reports you publish?

Milagros Miceli: It already shows when the community researchers talk and interview other workers: they know what to ask and how, and they establish rapport and trust immediately through their shared experiences. Good examples of this are the podcasts and documentaries on our website. Also, the zine about African women in content moderation, in which experiences of psychological, economic, and sexual abuse endured by female migrant workers at the company Sama in Kenya are shared, and the heartbreaking report that explores the mental health struggles of Meta’s content moderators. These are good examples of supporting community members in telling their own stories and coming up with new insights and better research outputs in the process.

netzpolitik.org: As you already mentioned, data workers usually have to sign non-disclosure agreements (NDAs). In the Data Workers‘ Inquiry, however, many workers name their employers, and some even appear under their real names. What risk are they taking to inform the public about conditions in the industry?

Milagros Miceli: Breaking non-disclosure agreements can have very serious repercussions for the workers. Just last year, a content moderator at Telus International in Essen, Germany, suffered retaliation for testifying about working conditions at the Bundestag. This not only signifies the loss of their income but could also lead to the loss of visas for the many migrants who depend on this job for their legal status.

Despite all these possible repercussions, our community researchers decide to speak up. This shows how pressing the issues being reported are and how important it is for the authors to reach a large audience. They are incredibly brave for doing this, but they are also relying on public pressure for protection and they certainly hope that after taking such a risk, their stories won’t be ignored.

Their commitment to sharing their stories shows how much trust they have placed in us and the project. Of course, this is a big responsibility for us, one that we don’t take lightly. We have offered each community researcher the possibility of remaining anonymous or anonymizing the companies they work for. Some of them have decided to do so, but most authors have decided to publish under their real names and name the companies. We work hard on protecting the information they provide and protecting them. For this, we have actively sought legal advice both in Germany and internationally, and with the organizations that fund this project. In addition, we’re in constant exchange with data protection and research ethics experts.

„Workers can collectively build up a counter-power to the corporations“

netzpolitik.org: The Data Workers‘ Inquiry is inspired by a questionnaire that Karl Marx used in 1880 to investigate the situation of the French working class. To what extent does digitalization with its global division of labour make it more difficult for exploited workers to engage in joint labour struggles today? Or can digital tools even be helpful here?

Milagros Miceli: Seeing that the Data Workers’ Inquiry is also an academic project, this question has both a theoretical and political answer. Considering theoretical analyses, the global division of labor by means of digitalization necessitates an expansion of the orthodox Marxist framework, away from a focus on the white industrial worker and towards issues of societal reproduction, intersections of race, gender, and class, colonial perpetuation, and the far-reaching exploitation of natural resources that all sustain platform capitalism.

The key role of data workers for the smooth functioning of AI reminds us of the fundamental Marxist claim that only human labor can create surplus value, irrespective of attempts to reduce them to mere appendices to machines. Data work should consequently be analyzed as a mode of production that exacerbates alienation by physically separating the workers from their products, which counteracts data workers’ political power to organize and exercise control over the means of production they employ as a globally dispersed workforce.

netzpolitik.org: If that was the theoretical answer, what is the political one?

Milagros Miceli: Without political pressure and public solidarity, workers are at the mercy of reprisals from technology companies. However, they can only exert pressure if they create channels of solidarity and collectively build up a counter-power to the corporations. And only then can they fight for fair working conditions.

Many of the community researchers already belong to trade unions. However, they are grouped together in various labour groups, which undermines their political power. In addition, many of them are dissatisfied with the large traditional trade unions and want to form their own unions.

And the use of technology can also help them in this struggle. Technology is not bad per se. It can actually help workers to connect and organize. Furthermore, some of our community researchers argue that data workers could do their jobs better if technologies were not used unilaterally to monitor and increase efficiency, but if they were instead used to optimize communication and collaboration between workers.

Data workers need better conditions and more recognition

netzpolitik.org: Many see a continuation of colonial exploitation in the digital economy: Hard work under precarious conditions is often outsourced to countries in the Global South. The profits flow predominantly to the Global North, both to the clients and to the operators of BPO companies and outsourcing platforms.

Milagros Miceli: According to the World Bank, there are between 154 million and 435 million data workers globally, with many of them situated in or displaced from the World Majority. The numbers have grown exponentially in the last few years with no sign of slowing down.

The larger concentration of data workers per country is still in the US, but the overwhelming overall majority is located in the Global South if we count countries like India and the Philippines and regions like Latin America, with Venezuela and Brazil at the forefront.

Before the Data Workers’ Inquiry, I conducted several studies with data workers in Argentina, Venezuela, Bulgaria, and Syria. In all cases, the requesters were located in the US and the EU. This adds another level of hardship for the data workers who have to work odd hours to cater to the client’s time zones and often don’t understand why instructions formulated in English are given to Spanish-speaking workers, or why the images they have to label depict objects that are foreign to them, for instance.

In other cases I observed, the images were strangely familiar, such as when refugee data workers displaced by the war in Syria were tasked with labeling satellite images of what they suspected was their region to be used for surveillance drones. This case shows how data workers’ experience is leveraged as expertise and their misfortune is used to perfect the same technologies that have contributed to their displacement.

netzpolitik.org: What needs to change in the tech industry in terms of outsourcing and what can people, civil society, and politics in Germany/Europe do to support data workers?

Milagros Miceli: We want to offer employees a platform on which they can put forward their demands. And most of them do so very clearly. They want better wages and working conditions, more stable employment contracts, and more support. This also includes psychological support for hazardous occupations such as content moderation.

Many of our community researchers are proud to contribute to technological progress and a safer internet, but want to be better recognized for it. Of course, this includes fair compensation.

We should therefore also stop asking whether an hourly wage of 2 dollars in countries like Kenya and Venezuela is a lot of money. Instead, we should be asking why the tech giants, which generate billions in revenue every year, don’t pay their employees more. After all, they are essential to their business.

0 Ergänzungen