A child, maybe six or seven, picks his nose with both fingers and makes silly faces for the camera. In the next picture he is eating a banana. Then we see a photo of a school report card, picture taken from a computer screen. It shows the child’s full name and the current grades in English and biology.

What looks like the digital photo album of a normal family has been freely available on the internet for more than a year – without the knowledge of the people concerned. A company that sells stalkerware – software for the secret surveillance of children and partners – has published these pictures and hundreds of intimate call recordings on the internet.

The photos not only show the child and his parents, their apartment, their bedroom, but also connect these to personal data such as names, e-mail addresses or medication prescriptions. The data has been on a server since April 2018 – without a password or other protection, freely available ot anyone with an internet connection.

For people „who are tired of being lied to“

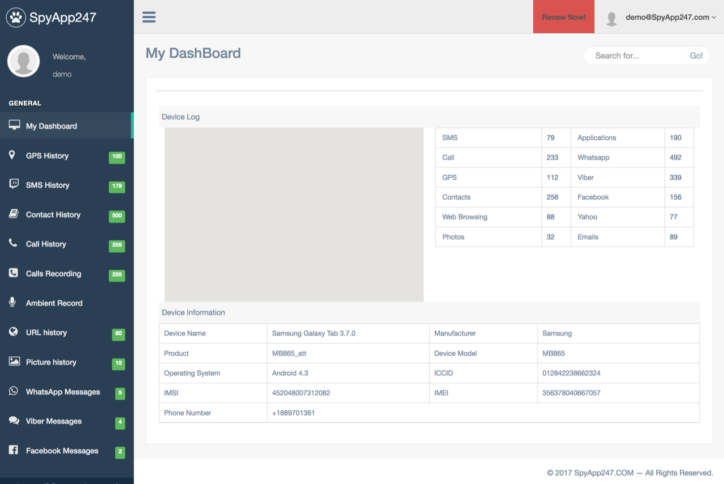

Responsible for this privacy disaster is a company called Spyapp247. It sells an app that allows you to spy on what another person is doing on their phone. The Android app records phone calls, chat messages, browser history, photos, allows access to the address book and tracks location data – without the affected person noticing. According to the manufacturer, even the microphone can be switched on remotely: The telephone becomes a bug.

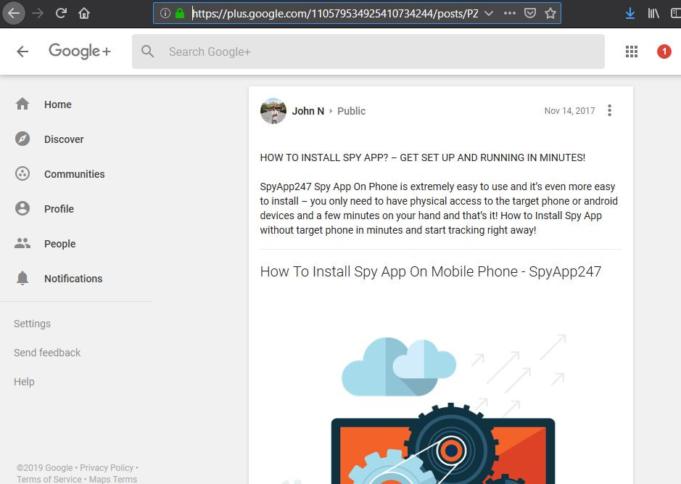

Spyapp247 markets the app on its website to people „who are tired of being lied to and cheated on,“ meaning: who want to spy on a partner. Civil rights organizations therefore call such apps stalkerware. But the company also advertises its apps as a tool for cautious parents to recognize „dangers to your children before they ever happen.“

Spyware manufacturer not reacting

It is hard to tell who installed the app in this case, and for what purpose, but it is likely that the data was obtained without the consent of the person targeted. In order to install the app, a person must have physical access to the device for at least a few minutes. Once the app is on the phone, it can collect all kinds of information in the background. The data is uploaded to a server and presented to the operator in a browser window.

One of the photos on the server shows the e-mail address the customer registered the app with. We considered alerting that person to the privacy breach. But by writing to this address, we would have reached the person who bought and installed the stalkerware – the perpetrator who may spy on a victim without their consent. We didn’t want to risk that, so we didn’t contact the customer.

Instead, we notified the manufacturer of Spyapp247 and pointed them to the open database. No answer. Finally, we reported the case to the company’s web hoster, who then took the site offline.

An old acquaintance

The current case is just the latest in a disturbing series of security breaches where manufacturers of stalkerware have either sloppily or not at all secured their customers‘ sensitive data. According to Motherboard, there have been twelve incidents in the past two years alone in which stalkerware companies have been hacked or inadvertently published data on the internet themselves.

The manufacturer of Spyapp247 is an old acquaintance as well. Earlier this year, he had already published another database with thousands of pictures and call recordings of his customers on a server. Back then it was another one of his products leaking the data, an app called mobiispy.

He did not react to multiple warnings and contact attempts by journalists back then either. The database remained openly available. It was not until Motherboard published the story that the company’s hosting provider intervened and took the thousands of pictures and audio files offline.

Many companies, one Gmail address

The exposed databases were found thanks to the work of Android security researcher Cian Heasley. He contacted netzpolitik.org after finding the pictures and phone recordings on the server. He had successfully guessed the URL based on what he knew about the data architecture of comparable apps.

Heasley works in Edinburgh for an IT security company and has been analysing the security of stalkerware apps for some time. According to his research, the manufacturer sells his apps under at least four other company names, including hellospy, 1topspy and maxxspy. The connection can be made because he has registered the domains for his products using the same Googlemail address. His name according to the registration: John Ngyuen.

Nguyen also runs his own YouTube channel, where he posts marketing videos for his various stalkerware apps. Until the end of the platform he even had a Google+ profile.

Nguyen’s branched-out portfolio of apps also includes hellospy, an app that is openly marketed as a tool for violent partners. Until recently, he was able to process the payment for these and other stalkerware apps via Paypal, even though they clearly violate the terms of use of the payment platform. Only after netzpolitik.org had repeatedly requested a statement from the payment service provider did Paypal block the accounts.

Morally doubtful, but legal

A man who takes so few security precautions to conceal his identity seems quite certain of his cause. And indeed, Nguyen doesn’t have much to fear. Spying on another person is a crime in Germany and many other countries. But since it is not illegal per se to sell spy apps, there is virtually no way to hold companies legally accountable.

They claim that their products are intended for legal purposes: to supervise employees with their explicit consent or to monitor your own underage children (in which case no consent is required). Corresponding legal notices can be found on the websites.

Miriam Ruhenstroth, who analyses the app security for mobilsicher.de, generally advises parents against monitoring children with such apps. „Most so-called parental control apps read usage data from the ‚child device‘ and transfer it to the provider’s servers – where the parents can then view it.“ There is always the risk that the data could be stolen or accidentally leak to the internet. „Especially when it comes to sensitive data such as the movement profile of one’s own child, we consider this risk to be unacceptable.“

„These companies don’t care what happens to the data.“

The manufacturer won’t have to fear a fine neither, even for such massive breaches of privacy as in the case of Spyapp247. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) also applies to companies located outside the European Union – in this case the domain is registered to a company in California. However, the manufacturers fall through the meshes of the law.

„The GDPR knows no manufacturer’s liability for data protection violations,“ writes Johannes Pepping of the State Data Protection Authority of Lower Saxony. „The person responsible in the sense of data protection law is basically the person using the software,“ i.e. the perpetrator.

Even in cases where it’s clear that a company stores data, as in this case, the chances of catching someone outside the EU are slim. It’s not clear where Nguyen lives or what citizenship he holds. The app’s website is registered to a California-based company.

„This just demonstrates what many of us who have researched stalkerware have been saying,“ Heasley writes in a chat with netzpolitik.org. „These companies don’t care about securing the data that they are helping steal from victims‘ devices.“

0 Ergänzungen

Dieser Artikel ist älter als ein Jahr, daher sind die Ergänzungen geschlossen.