The war in Ukraine highlights a new dimension in the importance of social media and the availability of information in general. Volunteers meticulously documented the massing of Russian troops before the attack and now the events of the war in Ukraine itself. The term for this activity is „OSINT.“

OSINT, Open Source Intelligence, refers to the analysis of freely available sources – which can be newspapers, videos, images, texts from social media and openly available information of all kinds. OSINT is a term derived from the world of intelligence services, Signal Intelligence (SIGINT) being the precursor, but has long since established itself as its own domain of research.

OSINT research on the Internet began with the democratization of the media public sphere and the start of citizen journalism. Projects like Indymedia laid a foundation at the turn of the millennium with open postings and the possibility of reporting directly from the street. Today, OSINT is used by journalists and journalistic organizations like Bellingcat, but also by a community that uses information from Telegram, TikTok and other openly available sources collecting the puzzle pieces to report and verify events that take place both in front of and away from the big TV cameras.

This is of interest to Peter, a pseudonym I use here to protect his identity. I’ve known Peter on Twitter for over a decade. He is always a quick, reliable and well-informed source about protest movements around the world. You could say, he always knows when people are taking to the streets in significant numbers somewhere, often before any media reports. And there’s a reason for that.

In on the action since Tunisia

„It’s also about the feeling of being in the thick of it,“ he says. The TV news is far too distant for him, there is a lack of detail. Often, he says, they only tell you what’s happening roughly, in two sentences. Their focus is on big politics, and so much is forgotten. Going deeper, together with others, especially people in the field, is something else, he says. „You learn a lot about political conflicts, but also about research methods.“

During the revolution in Tunisia in 2010/2011, Peter changed his news consumption behavior, he tells me during our two-hour conversation. Suddenly there were people with Twitter accounts on the streets, there were reports and pictures directly from the events, new sources, everything in real time. That’s when Peter and I first crossed paths on Twitter.

This new closeness of news fascinated Peter and hasn’t let go since. He was „there“ in Tunisia, during the Egyptian revolution, in the civil war in Syria, at protests on the Maidan, in Hong Kong, in Belarus and at many other rebellions and conflicts. There on the screen, often thousands of kilometers away and yet very close. „By now I wouldn’t even call it news consumption, it’s more of a search.“

Cross-disciplinary Community

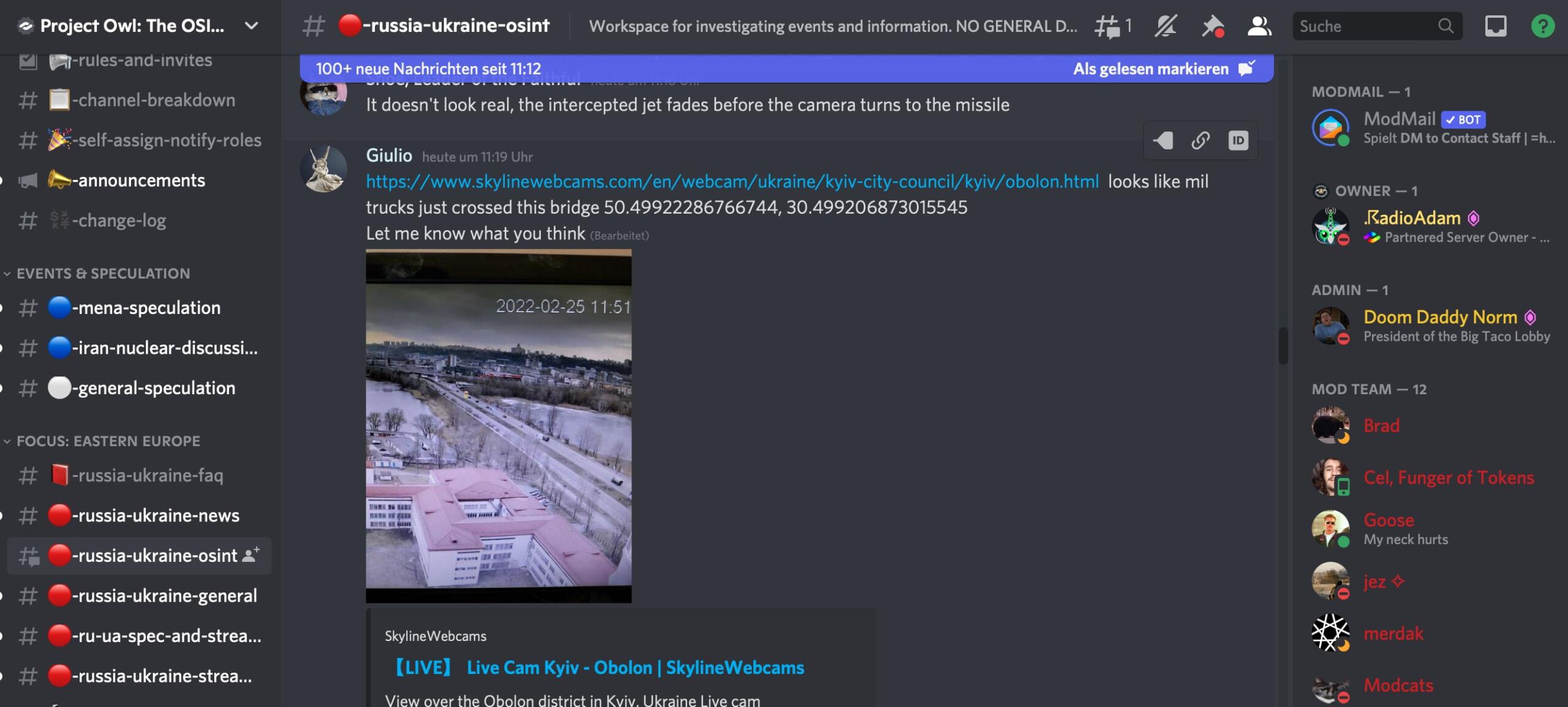

This search now involves thousands of people worldwide who are active in the OSINT community. They organize themselves on various Discord servers – and evaluate information that can be found openly on the net. Besides the Bellingcat server, there is Project Owl, Intel Doge and many more regional projects. They sometimes compete with each other, working in different ways.

„The community is completely cross-disciplinary,“ says Peter. There are people from the U.S., England, Israel, Palestine, Germany, Russia and the Donbass. There are young people in the community with a lot of time on their hands, but also older people like him, he says. Peter is in his mid-forties. Politically, the community is difficult to grasp, he says, because it is as colorful as the people. There are right-wingers and left-wingers. Most of them are open-minded in principle, liberal and Western. But many people are not political at all, although they do research into conflicts that polarize many people politically.

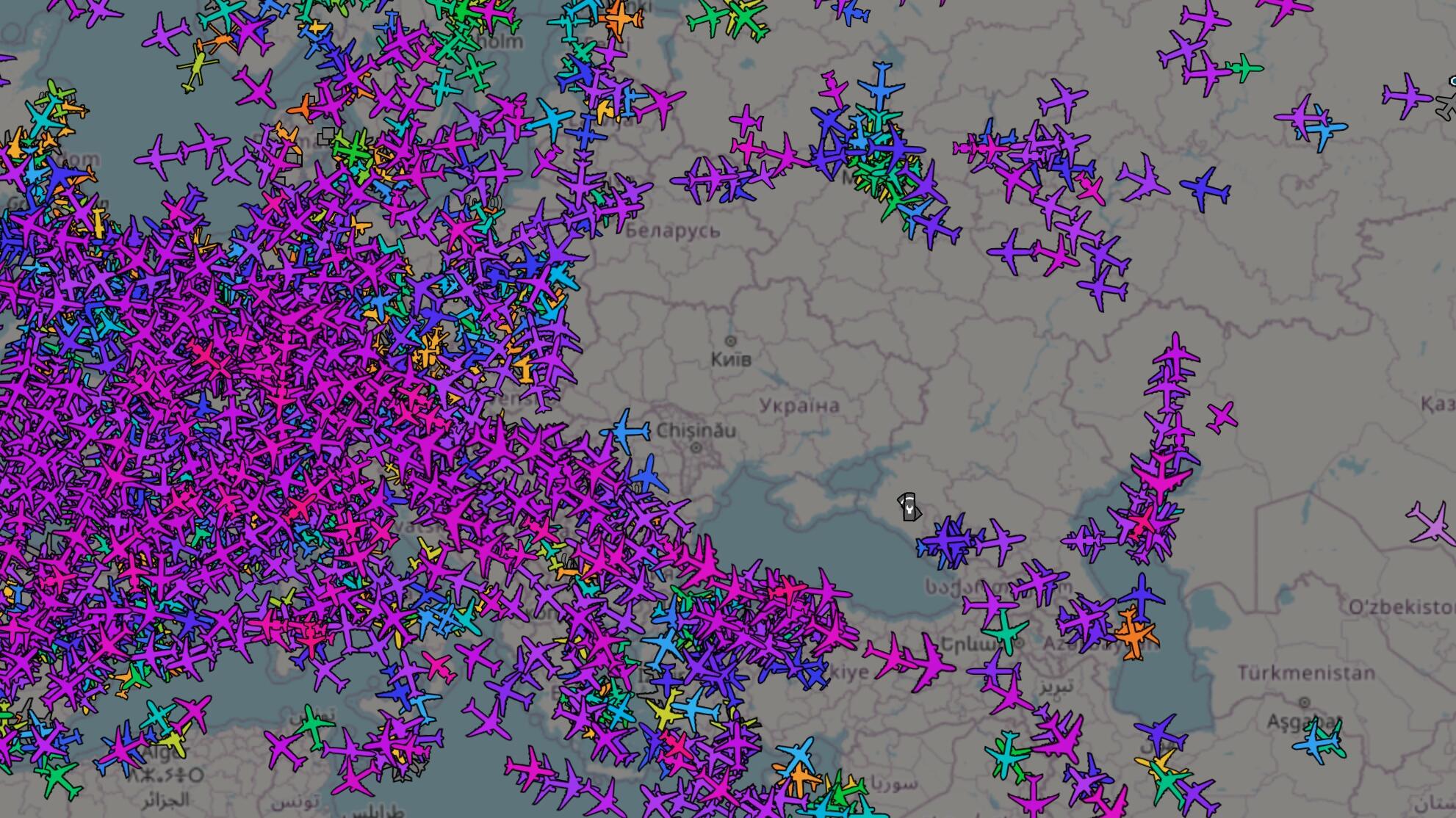

The vast majority of people are fundamentally interested in the conflicts, but mostly quite specialized. There are military geeks who know every type of tank, as well as people who follow airplane movements around the world and notice immediately when a certain plane takes off somewhere out of the ordinary. There are nerds who follow military movements all over the world and others who are not interested in that at all, but in quickly spreading a new, verified message. There are people who work in air traffic control or in the military, and after work, together with others, continue their work in a different way. They measure radar interference, which allows them to locate active military radars. And then there are many who love small-scale detective work.

Such detective work includes analysing video from TikTok, on which a tank column is seen driving, to a place and then to reconstruct the troop movements of the Russian army with this data. Such videos often come from completely irrelevant accounts, where suddenly, among the usual dance and meme videos, someone publishes how a long military column passes by. In the Ukraine conflict, most videos come from TikTok and Telegram, Instagram is insignificant, and Twitter is not really relevant. Someone from the community scans the social media and posts the new material on the Discord server. There, the research continues.

Google Streetview detective work

„I don’t mind spending 20 minutes driving down a Russian street on Google Street View on my computer,“ Peter says. He’s been doing just that in adhoc teams over the past few weeks. Finding street names, comparing houses, eye-catching buildings, water towers. Sometimes the teams use other tools, such as Trello project management software, to continue working on the cases in a calm, coordinated way.

This kind of detective work takes place accross various OSINT communities: Prominent buildings form a clue as to where exactly something was recorded. Other accounts check the plausibility of troop movements with Google mobility data, which actually shows civilian traffic jams or slow-moving traffic. If available, even recent satellite imagery can be compared to other footage – and a location then verified via a red fire truck.

Once again, case closed, a video is tagged with a location and time. Another piece of the puzzle correctly inserted and another detail made transparent in the larger flow of news. Verified information can then be further processed. The Centre for Information Resilience evaluates material and places the respective information on a map. In the process, it also debunks false information, for example when Russian attacks in Syria are passed off as current ones in Ukraine.

Mapping is only one of the disciplines of OSINT. Examining the metadata of files can reveal where they were created. Metadata is often written into the respective file by programs running on cameras, cell phones and computes. For instance, most music files contain information including the title and artist of the song in question. In the case of photos and videos, it can contain the date and time as well as the camera used or location information. Using such metadata, recently recorded television speeches by the leaders of the self-declared People’s Republics were shown to have been pre-recorded two days earlier. In the case of Putin’s declaration of war speech, however, the accusation that it had been pre-recorded proved to be false. Metadata is just one of the many pieces of information to consider, and it too should be treated with caution, as it can be easily edited.

Other people watch flight data websites like ADSBExchange, which show the positions of aircraft. This yields clues in conflict situations, such as aircraft deviating from their normal course, airspace being closed, or certain civilian aircraft taking off. Similar services are also available for ships. Data from weather stations, which are often located at airfields, can provide clues as to whether they are still operating regularly. For example, more and more weather stations at airports went offline after the Russian attacks. In a world of digital data, evidence can be drawn from almost everywhere. And this data is increasing in volume at an astronomical rate.

I ask Peter whether the process is something like working a puzzle. Yes, you could see it that way, but not only. It is a hobby and simply an interest. Sometimes this hobby is also very stressful. Peter can’t get videos from Syria out of his head. „That has left its mark. I don’t have to watch every video nowadays,“ he says. There is also an emotional connection through proximity, he says. And often, too often, he has seen hopeful protests for democracy develop only for the old regime to crush them. Through proximity and experience, Peter recognizes the first signs of such developments earlier than others. Sees how demonstrations become fewer and then completely silent.

More continuity through consistent community servers

The OSINT scene has changed. What used to happen mainly on Twitter and ad hoc networks, often for short periods of time, now takes place on Discord servers, which provide a place to go and more continuity for those interested. Peter is on Project Owl’s Discord, which recently cracked the 20,000-member mark. Even though there are more than 5,000 people online concurrently as the Ukraine conflict unfolds, Peter estimates the really active ones on that server to be a few hundred. Those who effectively contribute and push the cause. The rest read along, just drop in out of interest.

Several channels are currently dedicated to Ukraine. There is a news channel, which brings the latest findings, so that the users do not disturb the research channels with news requests. A FAQ channel explains the conflict. It is almost like a small Wikipedia, specialized in the respective crisis area.

The ad hoc meeting of people is still a core part of the OSINT community. You work with random people you don’t know, but who are interested in the same topic. You ask unknown native speakers if they can decipher an illegible street sign. You are happy when you solve a task together and can then feed it into the stream of news as a verified message.

In the community, there are those who are selfishly out for scoop fame and lots of likes and retweets, as well as those, like Peter, who are simply humbly fascinated by the shared research and deeper insights into the fine details of world events.

„Disinformation stands out quickly“

What can be observed in the community is a great division of labor and specialization. There are Twitter accounts like Conflict News or BNO News that report conflicts worldwide very quickly and reliably. Others keep Wikipedia pages up to date on ongoing conflicts, such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Peter has compiled a list of accounts for me that provides an overview of the different aspects of the scene for beginners. From these accounts you can go deeper, because the community is well connected. Peter warns, however, that accounts from the OSINT area have a different quality, some with a strong political bias. Often one does not know who is behind the account. For Peter, a frequent sign of quality is demonstrated by accounts that admit their mistakes and publish corrections.

But disinformation is hardly a problem in the community, says Peter. „Disinformation stands out quickly,“ he says. Many attempts on the servers would be recognized by experienced members in a short time. For instance, people who immediately see that the video of the tank column was from the uprising in Belarus, after all, and does not show current images in Russia. The community has also built its own defense mechanisms: Twitter accounts that have published misinformation in the past are shown on the Discord server with a note that they are not trustworthy. Many troll and fake accounts are blocked on the server and cannot be quoted at all. „The problem of disinformation is more on Twitter,“ Peter says. There, such accounts could rely on careless users forwarding fake news unchecked.

High-resolution satellite images are new

Over the years, the technical resources for conducting OSINT have become ever better. What is currently new, Peter says, is the availability of high-resolution and up-to-date satellite imagery. There are people in the community who invest hundreds of dollars in access to paid satellite imagery; others would have access at their jobs and then share the images in the community. „You’re researching something and all of a sudden someone in the chat asks: What place do you want to see?“ With satellite imagery, many tasks can be better solved.

Peter doesn’t believe intelligence agencies of large countries have an interest in the insights the OSINT community is developing. Such countries would have real-time satellite intelligence and much better information. They would not need to tap into the community’s intelligence. Of course, it cannot be ruled out that intelligence agencies also participate in the community or draw on its‘ information. There are also repeated accusations against Bellingcat of being too closely related to the USA and its intelligence services. Peter does not like secret services. He also thinks the term OSINT is pompous, reminding him too much of working in secret.

The big difference being that the international OSINT community does not keep its findings secret, but makes them available to the public. Together with journalists working in this field, it contributes to a greater understanding of crises, deepens our understanding of details, and organizes information that would exist, but without being classified or verified. Journalists, too, work with the community for this reason, drawing on this specialized knowledge and research results again and again. Some do this with reference to the community, others simply help themselves.

Peter goes back to work on the Discord server after our conversation. He has slept very little the last few days. Most recently, Peter and others have been searching for publicly available webcams that can be used to observe various points in Ukraine – and visualizing them on a map. There is a lot to do right now. It’s war.

0 Ergänzungen

Dieser Artikel ist älter als ein Jahr, daher sind die Ergänzungen geschlossen.