The Covid-19 pandemic is the greatest public health threat that Europe has seen in the last 100 years. Countries have thus introduced various levels of lockdown to reduce the number of new infections. Lockdowns, however, come at a great cost to workers, firms and families. Recent epidemiological models also predict that the epidemic will start anew once the lockdown is lifted (Ferguson et al. 2020).

Scientists have thus discussed a second approach to keeping the epidemic in check: app-based contact tracing. Several apps are currently under development, for instance in the UK and by a pan-European initiative, or have already been launched, as in Singapore.

Why would such an app be useful at all? We still don’t know many things about the coronavirus. The data so far suggest that about half of all infections occur before the dreaded symptoms of fever or a persistent cough appear. It is thus not enough to quarantine people once they show symptoms. To reduce infections, one would need to act quickly when a person is diagnosed with Covid-19 to find all people this person was in close proximity with. The risk of infection is highest if one has been within 1.5 to 2 meters of an infected person for at least 10 to 15 minutes.

If we could determine who had been in such close proximity, then one could ask freshly-infected, pre-symptomatic people to self-isolate and thus stop them from infecting more people. Mathematical models of the pandemic show that fast contact tracing combined with a large-scale virus-testing program might be able not just to delay the epidemic but to stop it entirely. This would also mean that the lockdown measures currently in place around the world could be slowly loosened up again. However, such fast contact tracing is not possible manually. Only a digital, largely automatic solution would help.

Epidemiology meets data protection

Some might argue that the demands of the Covid-19 crisis justify even extreme countermeasures. After all, this is about saving the lives and preserving the health of as many people as possible. Weakening data protection might be preferable to the far-reaching restrictions of personal freedom, and to the economic costs of the current lockdown. However, even in the face of an existential threat, we should interfere with fundamental rights as little as possible. Among the effective approaches, we should choose the one that least compromises fundamental rights. In particular, we believe that swift and efficient contact tracing is possible without collecting extensive amounts of data in a central database.

A contact tracing system can be set up in a way that would allow for most data processing to happen locally on users’ mobile phones rather than on a central server. Only the notification of users who have been in contact with an infected person would need to be coordinated centrally. And even in this case the necessary data could be processed in a way that would effectively preclude the central server from identifying the users. The system would also not require collecting any location data.

An example for this kind of Covid-19 tracing system is the “Trace together” app from the Singaporean government, which is already in the spirit of the “privacy by design” approach, and similar to what we present below (albeit with a few modifications). The European consortium PEPP-PT is following a very similar concept.

The fundamental idea is simple: It does not matter where people get in contact with an infected person. Be it on the bus or at work – what matters is proximity to a contagious person. This means that particularly sensitive location data, such as GPS or radio cell data, is actually neither necessary nor useful. Instead, the only data that matters is whether two people have come into close enough contact to risk an infection. This in turn can be detected via Bluetooth low energy technology, which can record whether two mobile phones are in close physical proximity. The general drawback of Bluetooth, that it can only reach across a few meters, becomes an advantage here.

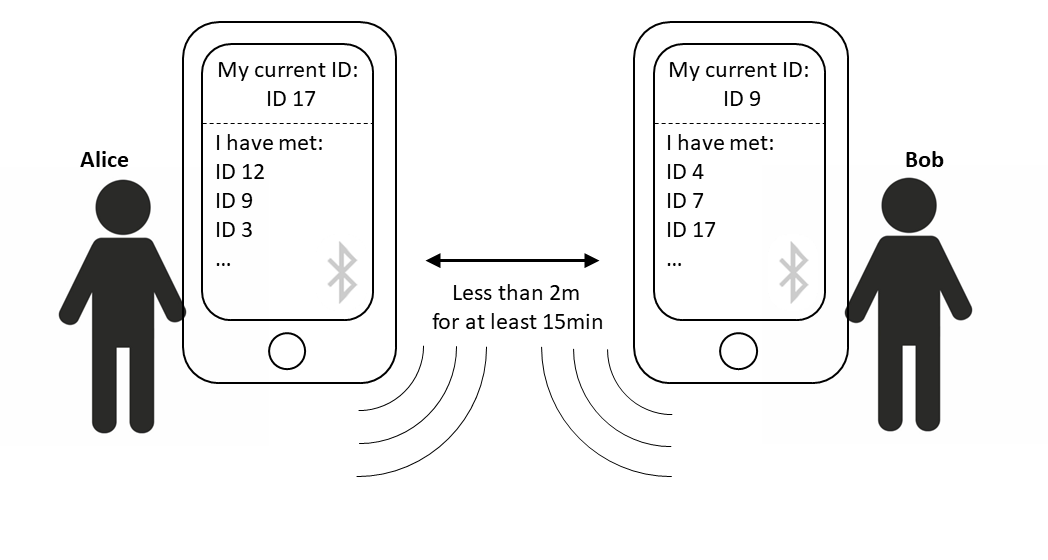

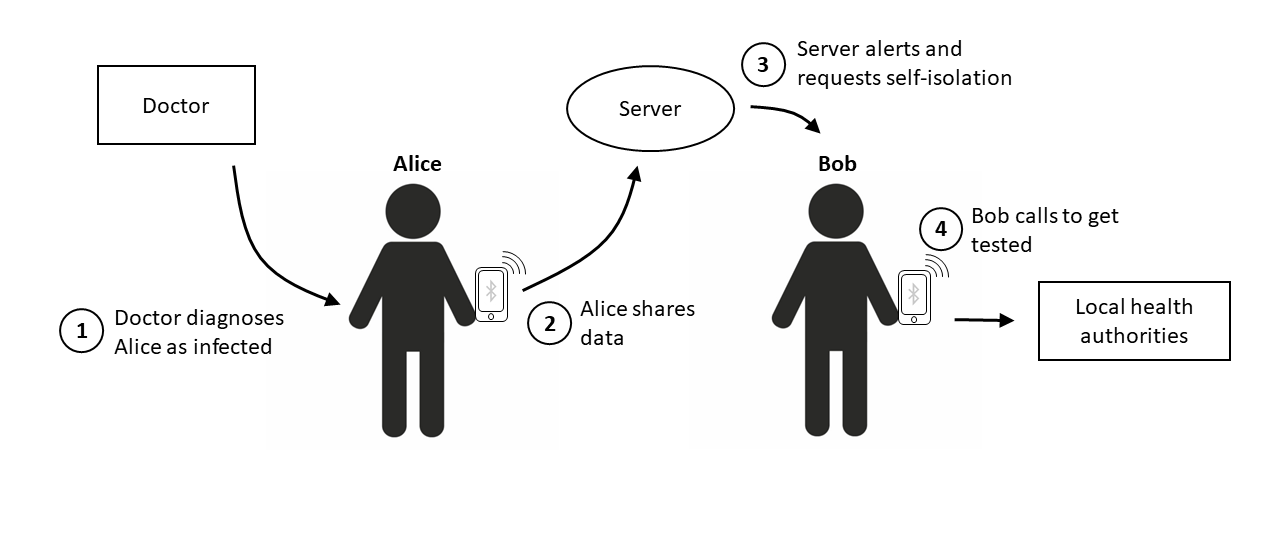

The tracking would work as follows: As many people as possible voluntarily install the app on their phone. The app cryptographically generates a new temporary ID every half hour. As soon as another phone with the same app is in close proximity, both phones receive the temporary ID of the respective other app and record it. This list of logged IDs is encrypted and stored locally on the users’ phones (see Figure 1). As soon as an app user is diagnosed with Covid-19, the doctor making the diagnosis asks the user to share their locally stored data with the central server (see Figure 2). If the user complies, the central server receives information on all the temporary IDs the “infected” phone has been in contact with.

The server is not able to decrypt this information in a way that allows for the identification of individuals. However, it is still able to notify all affected phones. This is because the server does not need any personal data to send a message to someone’s phone. The server only needs a so-called PushToken, a kind of digital address of an app installation on a particular phone. This PushToken is generated when the app is installed on the user’s phone. At the same time, the app will send a copy of the PushToken, as well as the temporary IDs it sends out over time, to a central server. The server could be hosted, for example, by the Robert-Koch-Institut for Germany or by the NHS for the UK. This way, it would be possible to contact phones solely based on temporary IDs and PushTokens whilst completely preserving the privacy of the person using the phone.

Once a phone has been in close proximity to an “infected” phone, the user of that phone receives a notification together with the request to immediately go into quarantine at home. The user will then need to contact the local health authorities to get tested for the virus as soon as possible so that, depending on the outcome, the user is either able to stop quarantining or all their contacts can be informed (see Figure 2).

During the entire process no one learns the identity of the app user: Neither the other users who got in close contact with them, nor the local health authorities, and not even the central server, since the app is not linked to an identity. Location data is neither recorded nor stored at any point of the process.

As mentioned above, we did not come up with this concept. Singapore introduced a very similar app and several European countries are working on comparable apps as well. We do not agree with all aspects of the Singaporean app and their practice of contact tracing. For example, every app installation in Singapore is linked with the user’s telephone number and is thus identifiable – something that is not strictly necessary and thus, for data protection reasons, should be rejected. Nevertheless, we like the general concept. The recently published pan-European contact tracing standard PEPP-PT looks promising and might prove to be a legitimate implementation of the privacy-friendly tracing approach outlined above.

Such an app could implement contact tracing much more effectively than a system that relies on radio cell or location data, since neither of these two data sources permit determining a person’s position with the necessary precision of two meters maximum. At the same time, such a concept would comply with existing data protection regulations.

Data minimisation begets acceptance

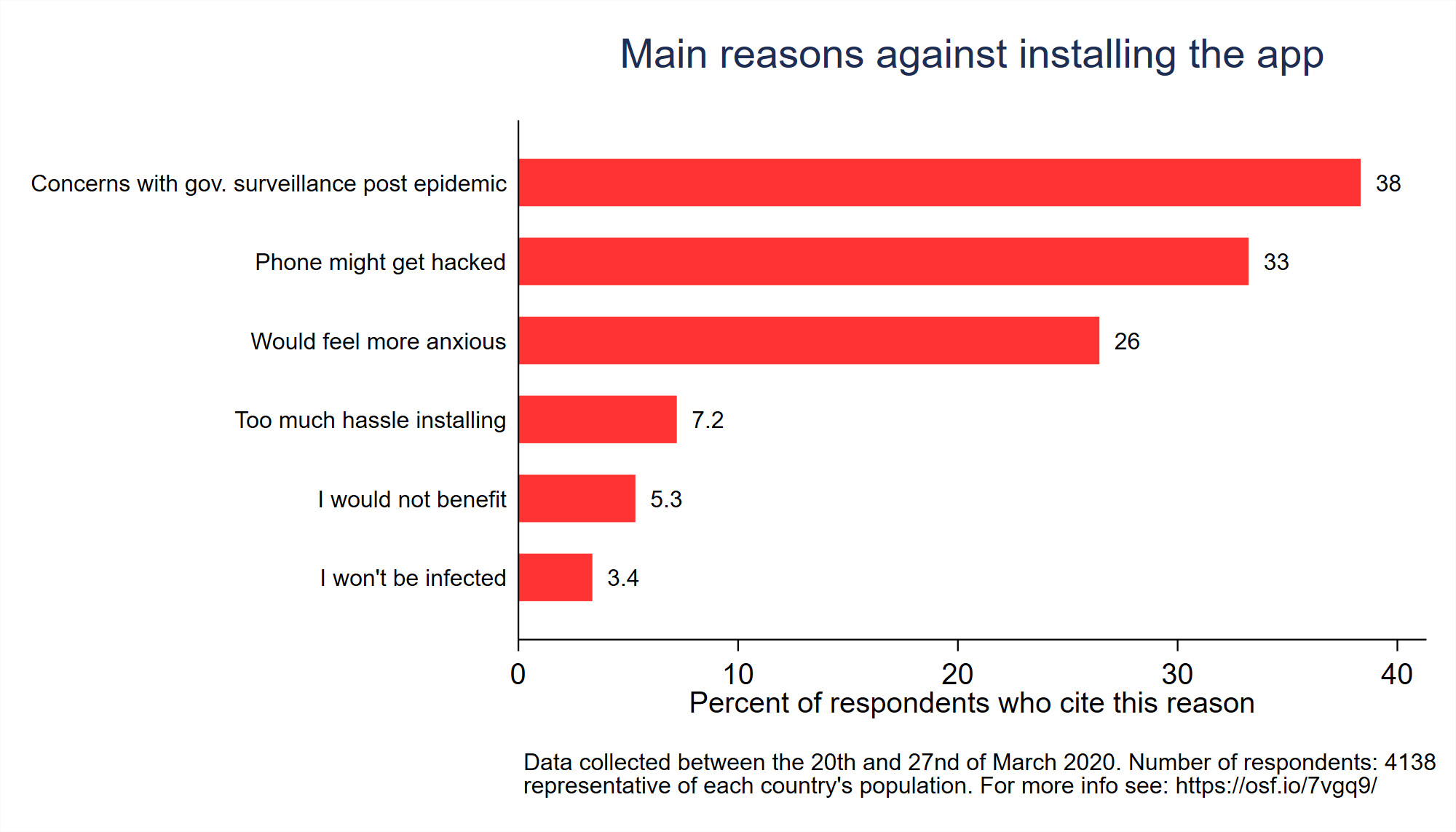

In the case of contact tracing, the approach that requires the least amount of data also seems to be the most effective epidemiologically. This is because an app like the one described above would be better suited to determine who actually was in close proximity than any of the other proposed solutions. Moreover, even digital contact tracing systems need users to cooperate (by installing the app and carrying their phones with them) for any chance of success. Consequently, the effectiveness of any contact tracing system depends on public support. There is reason to believe that the level of support can be increased by opting for a data-minimising solution. A representative survey across four countries shows that about 70 percent of respondents would install an app like the one described above on their phones (disclosure: Johannes Abeler, one of the co-authors of this article, is also the lead author of the survey study). The reason most frequently brought up against an installation is the worry that the government could use the app as an excuse for greater surveillance after the end of the epidemic (see Figure 3). If the government wants as many people as possible to install the app, it should take these concerns seriously and refrain from using location data. Contact tracing works without it.

Conclusion: Proportionality instead of „whatever it takes“

In the current crisis, we will have to endure more and deeper encroachments on fundamental rights than we are used to. Still, there is no reason to tolerate such encroachments to a greater extent than strictly necessary. Even under the current time pressure, it is important to find solutions that minimize data processing as far as possible. We have shown above that this is possible for the case of contact tracing. As the pandemic progresses, many other challenges will emerge. For each of them, one will have to check which data processing is necessary to address them and which ones can be avoided.

Trying to find the data-minimizing solution does not just protect fundamental rights. Such solutions will often increase the effectiveness and efficiency of the respective data processing system. Only if people trust a system – because it doesn’t spy on them – will the system find broad support in the population.

Johannes Abeler is Associate Professor in the Department of Economics at the University of Oxford and Tutorial Fellow at St. Anne’s College.

Matthias Bäcker (Twitter) is Professor of Public Law at Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz.

Ulf Buermeyer (Twitter) is president of the non-governmental organization Society for Civil Rights (GFF.NGO) and desk officer at the Department of Justice of the Federal State of Berlin. This publication does not necessarily reflect the position of his employer.

Where you got the parameter 15 minutes from?

Any study source?

There is no clear cut-off for becoming infected or not. The longer and the closer you are to an infected person, the higher is the risk that you become infected. If the app only sends one of two messages, either „all clear“ or „you are at risk, please quarantine“, then the algorithm behind the app would need to use such cut-off parameters. However, my understanding is that the algorithm would use more information than just distance and time length of the interaction. The infectiousness of the diagnosed person might also be used, for example. The parameters mentioned in the article are (reasonable) examples but can and will change as we learn more about the virus.

Am I the only one to see here an antipattern repeated that we should remember all too well from the blockchain disaster and try to avoid at all cost? Virtually every article trying to sell blockchain architectures as the next big thing ignored all real-world requirements, particularly all socio-technical and application consideration, and instead described in meticulous detail the technology allegedly about so take over the world and solve all kinds of problems. Alas, this technology was built on rather obvious misconceptions about the application context, such as an unwillingness to accept regulation and institutions.

This article here sounds similar, telling us a lot about Alice and Bob and Servers and privacy by design, but very little about contract tracing as an institutional activity with consequences. Why would one even think, for example, of a scheme involving phones issuing orders to people without any transparent justification? Have you tried to apply any of the proposed approaches to algorithm ethics before you set out to devise technology that works only if people becomes slaves to machines?

Phones aren’t giving orders to anyone – they’re giving good advice.

How would anyone have a problem with a system that relies entirely on privacy and voluntary participation?