Raphael was twelve years old when he started working at a cobalt mine near Kolwezi. Just like most of the kids from his village in the southern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), he needed the money. At age 15 Raphael was strong enough to dig deeper tunnels and work deep underground at the mine. Two years later, on April 16th 2018, he died. The tunnel he was working in had collapsed, his aunt Bisette later told the Guardian. 63 people were buried alive. No one survived the collapse.

It was not the first time that workers died mining cobalt, a raw material that has become indispensable for the functioning of modern technologies. In fact, human rights defenders have been warning about the horrible working conditions and the use of child labor in the cobalt mines of the country in central Africa for years. But this time was different. Bisette, who had been raising Raphael after his parents died, decided to fight back. The human rights firm International Rights Advocates filed a lawsuit on behalf of her and 13 other families from the DRC whose children died or suffered life-changing injuries because of accidents in the mines.

Series on Digital Colonialism: Other articles of this series can be found here. >The German version of this text can be found here<.

This lawsuit was different than any other. For the first time in history it was not filed in the DRC, but in Washington DC, bringing US tech companies to court for having business partners in their supply chain that are allegedly responsible for the death of thousands of miners. The class-action lawsuit accused Google, Apple, Microsoft, Dell and Tesla of aiding and abetting in the death and serious injury of children working in cobalt mines. It states that the defendants had “specific knowledge” that the extraction of cobalt is linked to child labor.

The lawsuit sought damages for employing child labor and compensation for unjust enrichment. It was supposed to hold tech companies accountable for the terrors hidden in their supply chain. It should have brought justice to a global economy that extracts resources from countries of the global south and adds the value to western companies. And it failed.

Congo’s „black gold“

Cobalt is an essential raw material used for rechargeable lithium-ion batteries, which are needed to power electronic devices. Its relevance for the tangible basis of today’s information society is extremely high. Without cobalt, no lithium-ion batteries. Without lithium-ion batteries, no smartphones or laptops. (Correction: Initially this paragraph also referred to electric cars. Thanks to our readers for pointing out that some manufacturers of electronic vehicles started to use lithium iron phosphate cells as an alternative.)

In the last decade, the global demand for this resource tripled in size and is expected to double by 2035. In 2021, the global cobalt market size was estimated to be a whopping $8.572 billion. With a global shift to a green economy and an increase in the use of electric vehicles, its demand is expected to get an even higher boost.

The DRC has more than half of the world’s cobalt resources and is home to over 70% of the world’s cobalt mining. However, despite being the largest global supplier of the „black gold”, as they call it, Congo is still one of the poorest countries in the world. It was estimated by the World Bank in 2018 that 73% of the Congolese population, amounting to 60 million people, lives below the World Bank’s poverty line of less than $1.90 a day. One out of six lives in extreme poverty.

Bisette says that her nephew Raphael, who died trapped under a cobalt mine, started working as a miner because they could not afford to pay his monthly school fees of $6 dollars. He was one of 255,000 people employed in the cobalt mines in Congo. According to the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund, UNICEF, 40,000 of them are kids. Some child workers are as young as seven years, Amnesty International claims. Typically, a worker at a mine earns less than $2 dollars a day.

These workers do the physical labor that so-called digital companies like Apple, Tesla, and Microsoft are built upon. But the billions of dollars of profits that the global tech giants make annually never translate to better working conditions for the workers in these mines.

Life-threatening working conditions

Miners in Congo work in extremely dangerous and life-threatening working conditions. At times, workers spend up to 24 hours in tunnels without any protective gear. The tunnels are so narrow that only one person can pass at a time and are so small that the miners cannot even properly stand. They do this under constant fear of a tunnel collapse.

However, that is not the only danger. There is also the lack of oxygen underground. At times the miners work as deep as 25 meters below the ground with the nearest opening as far as 100 meters away. To reach the chamber where they start mining, they need to navigate extremely treacherous routes which are hard to climb down and up. The temperature, which is hot at the surface, becomes a burning furnace underground. At the bottom chamber, they start chipping away cobalt using a crowbar. But they must work fast and quickly ascend because at such a deep level there is only 20 minutes’ worth of oxygen. But because they can only collect a handful of cobalt within 20 minutes, these miners descend into the mines several times a day. Each time running against the clock for their lives.

As if this was not enough, cobalt extraction in Congo has been linked with human rights abuses, including the sexual abuse of children. The Australian Broadcasting Corporation ABC for example reports the case of a female child worker. She was eleven when she was forced to work at a mine due to poverty. At age 15 she had a young child and had lost her husband in a car accident. Soon thereafter, her boss at the mine started demanding sex. At first, she refused but that only resulted in her boss making her job more difficult. Eventually, she gave in. “I was sexually abused by my boss almost every week,“ she says. „I could not give up the job because I needed the money to support my children and my parents.“ She says that she was made a team leader a week after she was forced to sleep with her boss where she earned more money, but she says she „was like a sex slave to my boss and I had a child with him.“

Poisonous for workers, kids and residents

Furthermore, recent studies imply that exposure to toxic pollution is causing birth defects in the babies of cobalt miners. Not enough investigations have been conducted on the harmful effects of toxic pollution due to mining activities in Sub-Saharan Africa but the doctors and researchers see a connection between birth defects and metal pollution. The Guardian reports that research published by The Lancet Planetary Healthy in April 2020 „found that the risk of birth defects greatly increased when a parent worked in a copper and cobalt mine.“

But the harmful effects of mining are not just limited to miners and their children, but also to the residents who live in the vicinity of the mines. A study found that residents who live near the mines have 43 times higher levels of urinary concentration of cobalt compared to the control group that lives outside the mining area. Human Trafficking Search, a global resource and research database on human trafficking reports „lead levels five times as high, and cadmium and uranium levels four times as high“. The levels among children living in the vicinity of the mines were even higher.

All these terrors cannot stop the miners from working in the mines, sometimes they even bring their infants along with them. Siddharth Kara, an anti-slavery economist on whose research the lawsuit was filed, speaks of a girl called Elodie. Aged 15, she is an orphan and has a two-month-old child whom she carries tightly wrapped around her back while she works at one of the cobalt mines. Kara says that the child inhales „lethal mineral dust every time he takes a breath“. Elodie earns a mere $0.65 for her back-breaking entire day’s work. She lost both her parents to the cobalt mines.

According to Kara, stories like Elodie’s or Raphael’s are no exceptions in Congos cobalt mines, they are the norm. The horrible working conditions and human rights violations mentioned here formed the backdrop of the lawsuit filed by the Congolese families. Although reports of child labor at the cobalt mines in Congo are not new and the connection between the defendant tech giants and the purchase of cobalt linked to child labor is not hard to make, it was the first time that western tech companies were brought to court for this.

More than an echo of colonial practices

According to the plaintiffs‘ claim, Apple, Google, Tesla, Microsoft and Dell buy battery grade cobalt from Umicore, a Brussels-based metal and mining trader, which buys cobalt from Glencore. This UK mining company owns the mines where Raphael died in the collapsing tunnels, reports the Guardian. Apple, Dell, and Microsoft apparently bought cobalt from Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt, a major Chinese cobalt firm, which also owns mines that employed child labor.

Long before the filing of the lawsuit, there have been reports of the use of child labor and human rights violations in the Congolese cobalt mines. But the defendants in the lawsuit have largely maintained that they had not been aware of reports of the use of child labor for the extraction of Congo. Dell for instance claimed that “We have never knowingly sourced operations using any form of involuntary labor, fraudulent recruiting practices or child labor”. Google on its part maintained that “Child labor and endangerment is unacceptable and our Supplier Code of Conduct strictly prohibits this activity.”

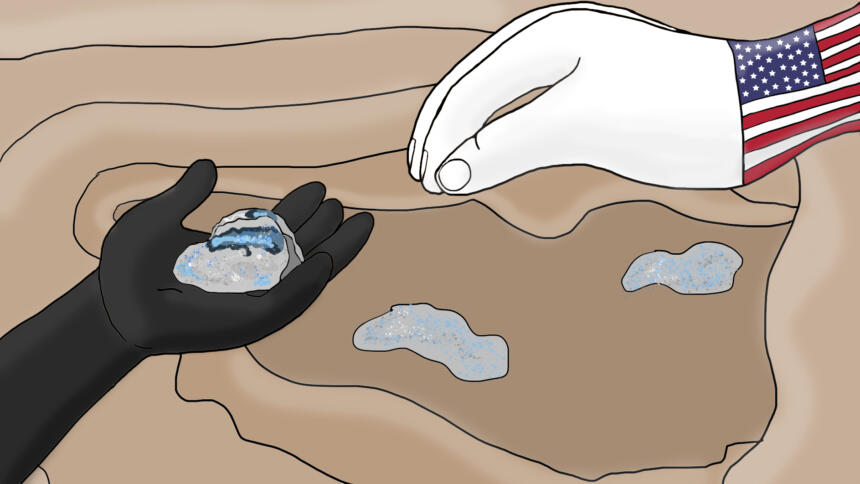

From an overview of the lawsuit, the connection seems to be straightforward, and it appears to be more than an echo of the colonial practices of exploitation of foreign natural resources and labor. The raw material from the global south is extracted and exported to the capitalist centers in the global north where it is converted into finished products. The finished products in the end are so expensive that people from the countries where this raw material is extracted cannot even afford to buy them.

An important element of colonial rule has been for centuries the foreign ownership of the mines and natural resources to the exclusion of the people of the colonized nations. Such a system led to the creation of colonial dependencies and poverty that the colonizers exploited, which forced the locals into slavery or slave-like working conditions for mere survival. Today, the mines in Congo from where cobalt is extracted are owned by foreign companies which exploit the extreme poverty to force the people to work in extremely dangerous conditions at slave wages.

And lastly, the colonizers enriched their empires beyond imagination all the while exploiting and plundering local economies without ever facing any accountability.

„Mere speculation, not a traceable harm“

Apparently, this never changed. As clear as the connection between the tech companies and child labor was to the defendants – US District Judge Carl J. Nichols did not see it. In November 2021 he tossed away the lawsuit against Apple, Tesla and Co. saying there is not a strong enough causal relationship between the firms’ conduct and the miners’ injuries. „The only real connection“, Judge Nichols stated, „is that the companies buy refined cobalt”.

Framing the deaths of child workers as “tragic events”, the judge denied both the right of Congolese families to bring a lawsuit to a US court and the responsibility of US companies. “It might be true that if Apple, for example, stopped making products that use cobalt, it would have purchased less of the metal from Umicore, which might have purchased less from Glencore, which might have purchased less from CMKK, which might thus have instructed Ismail to stop purchasing cobalt from artisanal child miners, which might have led some of the plaintiffs not to have been mining when their injuries occurred,” the judge said. “But this long chain of contingencies, in all its rippling glory, creates mere speculation, not a traceable harm.”

For all who had hoped for this case to bring some justice to the global economy and to the families of the deceased, the trial ended in a tragedy. For all we know, the working conditions are still the same. Children die, mining cobalt for our devices. For Raphael’s aunt Bisette and the other families there only remains one cold comfort: It was „the first time that the voices of the children suffering in the dark underbelly of one of the richest supply chains in the world“ were heard in a court of law, as researcher Siddharth Kara wrote.

Series on Digital Colonialism

This article is part of a series on Digital Colonialism. We will cover different issues pertaining to the dominance of digital space in the global south by a handful of powerful countries and major tech companies. Over the past several years, scholars and activists have been increasingly writing on how this handful of firms use digital technologies to create dominance that extends itself to socio-political and economic space undermining the sovereignty and local governance in countries of the global south.

These scholars term this phenomenon as digital colonialism. They argue, that while the mode, scale, and contexts may have changed, colonialism’s underlying function of empire building, value extraction and exploitation of workforce remain the same.

Read other articles from the series:

0 Ergänzungen

Dieser Artikel ist älter als ein Jahr, daher sind die Ergänzungen geschlossen.