Mikko Hyppönen is a computer security expert for more than two decades and is head of investigation at F-Secure corporation in Finland. Mikko publicly comments on and writes about malware, hacktivists and governments for many years. He is also advisory board member on Internet security at Europol.

This August, his new book If It’s Smart, It’s Vulnerable was released. We publish an excerpt.

Excerpted with permission from the publisher, Wiley, from If It’s Smart, It’s Vulnerable by Mikko Hypponen. Copyright © 2022 by Mikko Hypponen. This book is available wherever books and eBooks are sold. All rights reserved.

Law Enforcement Malware

The concept of law enforcers using viruses and other malware to infect citizens’ computers may seem far-fetched. However, this is a commonly utilized technique everywhere in the world.

In the end, it comes down to which rights we citizens want to grant the authorities. If we feel that the trade-off between safety and privacy is balanced, we will grant special rights to the authorities. On the other hand, if the trade-off is one-sided, we will not. When landline phones became common, law enforcers wanted the right to tap them. After the emergence of mobile phones, the police were permitted to listen in on the mobile network. Then came authorizations to track text messages and emails. However, when powerful encryption systems became the norm, tracking traffic was no longer enough, as nearly all online traffic intercepted by the police was encrypted – leading to the right to install malware on suspects’ devices. This bypasses encryption, as messages are read before they are encrypted or after they are decrypted.

But how is malware installed on a suspect’s device, once law enforcers are authorized to use such software? Many techniques are available, but most are quite different from those used by cybercriminals. The police may apply for a warrant to break into the suspect’s home and physically infect devices, or may cooperate with a local Internet operator to modify software that the suspect downloads from the Internet.

It seems slightly strange that the same police officers we, at F-Secure, help to catch cybercriminals also use malware in their work. I have discussed this with the officers, saying that, while I understand their need to use malware, we will nevertheless try to prevent it. I have also told them not to expect our help if they do use malware. We cannot ignore viruses written by the authorities, regardless of how good the intentions are. If law enforcement wants to use malware, that is their business.

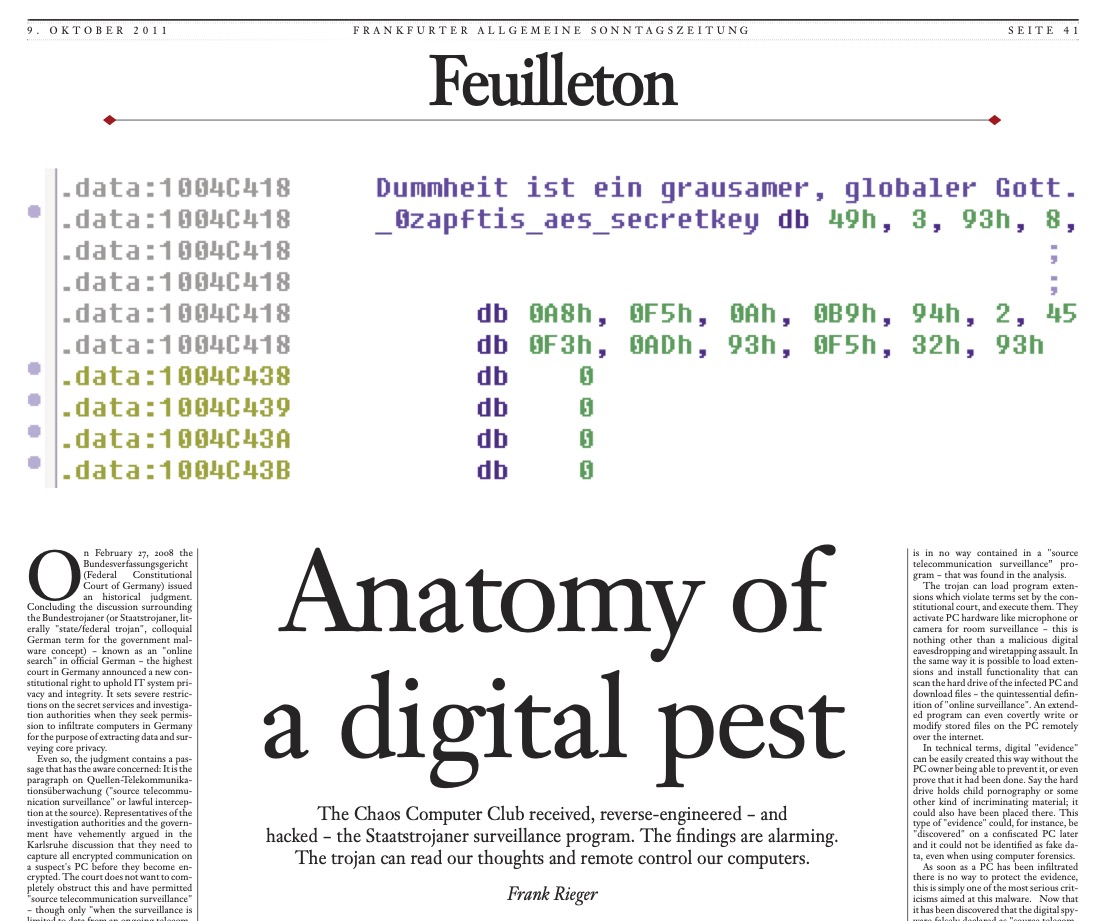

Case R2D2

The first time we encountered law enforcement malware was in October 2011 – malware known as R2D2 or 0zapft, which had been created by the federal government of Germany. When we published the detection update for this malware, I wrote about it in our blog, cagily mentioning that we had been sent a sample “from the field.” I can now disclose the truth. I was contacted by the Chaos Computer Club (CCC), a German association promoting freedom of speech regarding technology. Their experts were helping a person who was facing charges for customs violations. The accused suspected that their laptop had been infected by German border guards at Munich airport, upon the suspect’s arrival in Germany.

CCC’s technicians found complex malware running in the background of the computer and monitored the operation of four programs: Skype, Firefox, MSN Messenger, and ICQ chat. The club was unsure about what would happen when the case became public, particularly whether antivirus software would identify the malware, which was not criminal software. In fact, it was the polar opposite.

CCC’s representatives called me because, in a public speech, I had made it clear that we must protect our users, regardless of where malware originates. Our definition of malware is technical, not political or societal. Malware is software that the user does not want on their computer, and R2D2 met this definition. The CCC wanted to ensure that, when the R2D2 case became public, a well-known and reliable antivirus solution would not hesitate to add recognition of it, making it easier for other companies in the field to follow suit. We did just that. When the German press heard about the case, it became international news within an hour. We had built our detection update in good time and published it simultaneously with my blog post, where I presented the rationale for stopping malware even when written by law enforcers. Three hours later, Avast antivirus software started to remove the malware. One hour after that, McAfee did the same, followed by Kaspersky. By the evening of the same day, practically everyone had done the same. CCC’s tactics had worked.

Cracking Passwords

When a suspect is arrested and their devices are locked with an unknown password, there is only one option left: cracking the passwords. Although data traffic protected with modern encryption is practically impenetrable, an attempt can be made to decrypt files or file systems by trying all possible passwords. This can often be expedited by distributing the task between dozens or even hundreds of computers.

Authorities have pretty impressive decryption systems for this purpose. An office building in The Hague, for example, has decryption hardware the size of a supercomputer, which needs its own power station. Hardware like this allows millions of password options to be tested per second. Nevertheless, a single encrypted file can take months to open.

Automated decryption systems use a clever tactic for speeding up this operation. If a password-protected file is found on a suspect’s hard drive, all files on the drive are indexed, and all individual words are collected from each file for testing as passwords. If none work, all discovered words are tested in reverse, and if this does not work, the drive is scanned for any unused areas and deleted files, and words inside them are tried. On surprisingly many occasions, this will decrypt the files.

When a Hacker Spilled Her Coffee

Hardened cybercriminals know when they are being hunted. Many of them have prepared for an eventual arrest, building systems to destroy the evidence.

A Russian botnet criminal ran a computing center inside his two-bedroom apartment in St. Petersburg. He had his door changed to a sturdy metal door attached to a heavy metal frame. When the local police arrived to arrest him, Igor had plenty of time to start deleting files from all his servers. Being unable to get through the door, the police eventually made a hole in the wall next to it. Igor was found in his kitchen. On the hot stove, he had a kettle, and in the kettle he had his memory cards and SIM cards from his mobile phones. Their contents could never be restored.

The best tactic is to distract a criminal, preventing them from destroying or locking their devices upon arrest. In an arrest coordinated by EUROPOL, the suspect was sitting in a café with a laptop when a female undercover officer sat at the same table, spilling her coffee a few moments later. The suspect stood up, at which point a male officer waiting behind stepped forward and whisked away the unlocked computer for forensic analysis.

0 Ergänzungen

Dieser Artikel ist älter als ein Jahr, daher sind die Ergänzungen geschlossen.